Philippe Lucas PhD, Victoria, Canada

When Philippe Lucas got a hepatitis C diagnosis as a college student in 1995 he could not have imagined it would put him on a path to becoming a groundbreaking patient advocate and being named ASA’s 2021 Cannabis Researcher of the Year.

At that time, hepatitis C didn’t even have a name. It was just non-Hep A, non-Hep B -- an incurable progressive disease that slowly destroyed the liver. The disease advanced slowly enough that many people who received the diagnosis as older adults didn’t need to worry about that. But Philippe had unknowingly contracted it through a blood transfusion during surgery at 12, so liver failure was a real possibility by the time he reached his 40s or 50s. Soon after his diagnosis, he developed symptoms including nausea and appetite loss. When he asked his doctor if he was dying and what he could do to fight it, giving up alcohol and tobacco was the answer.

“I’m French Canadian, so those were my drugs of choice,” Philippe says. “But I was resigned to giving them up and went cold turkey.”

He turned to cannabis to manage the withdrawal and cravings. It proved effective, but he was worried about how it might affect his liver, so he started looking up the medical research on cannabis. What he found shocked him.

“The research contradicted what the government had told me,” Philippe says. “I discovered that cannabis was helpful for not just my symptoms but also viral infections themselves. It wasn’t the lesser of two evils—it was helpful!”

Within a few months, Philippe was feeling better physically, emotionally, and psychologically than he had in a long time. But in the late 1990s, finding a safe, consistent supply of cannabis was not easy.

“I thought, if college students have trouble getting cannabis, what’s a 65-year-old woman with cancer going to do?” Philippe remembers. “After looking at the compassion clubs that were developing elsewhere in North America, like Denis Peron’s in San Francisco and the BCCCS in Vancouver led by Hilary Black, I decided to start one to help patients.”

The Vancouver Island Compassion Society (VICS), one of Canada’s first dispensaries, opened its doors in 1999. Philippe would serve as its executive director for the next decade. The research he conducts today started with things he heard from the patients at VICS.

“We saw an influx of patients with HIV and Hep-C resulting from their IV drug use,” Philippe says. “They had cannabis recommendations for those conditions, but they shared with us that it was reducing their cravings for opioids, meth and alcohol. I realized that was flipping the script on the gateway theory. Cannabis is exactly the opposite. It’s an exit drug.”

Patients’ patterns of cannabis use and its impact on the use of other substances became the focus of his research as he progressed through a master’s degree to his PhD at University of Victoria. Lending support to the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), Philippe got a chance to visit Israel to share his experiences with policy-makers, eventually doing the same in Uruguay, Columbia, Australia, Portugal, and elsewhere.

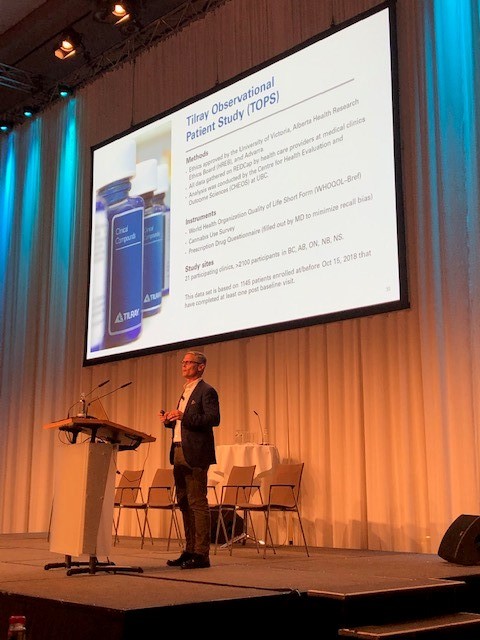

He has now published over two dozen academic articles on medical cannabis and the patient experience and serves as vice-president, Global Patient Access & Research at Tilray, the world’s largest international cannabis company. But the road to these successes has not lacked struggle.

Within a year of opening VICS, local police raided the facility and Philippe’s home, resulting in three counts of drug trafficking. As his case was working its way through the courts, a separate constitutional challenge to Canadian law by cannabis patients resulted in courts declaring an exception must be made for medicinal use.

Philippe qualified as one of the country’s first legal patients, but the process was cumbersome, entailing a 32-page application, certification by both his primary care physician and two specialists, and an 18-month wait for processing.

“What the government had established was not viable for cancer patients or many others who are seriously ill,” Philippe says. “Their ‘access regulations’ were an oxymoron --they were designed to stop people from having access.”

Nor had the government established a way for qualifying patients to legally obtain cannabis except by cultivating it, which takes time, skill, location, and physical wherewithal. As a result, Philippe continued to provide cannabis illegally through VICS, even as he awaited sentencing on the trafficking counts.

Philippe had pled guilty to all, just as he had cooperated openly and completely with police, explaining how VICS operated and why. When it came time for sentencing in 2002, the judge granted Philippe an absolute discharge, praising his principled work doing for patients what Health Canada had failed to do. That ruling paved the way for future dispensaries in Canada.

Nonetheless, police returned to raid VICS’s production and research facility a few years later, ironically seizing the low-THC hemp plants VICS had developed as a placebo for medical trials.

Philippe’s experience with the courts had made him all the more interested in the Ed Rosenthal case that led to the founding of Americans for Safe Access in 2002.

“I was incredibly inspired by what I saw ASA doing,” Philippe says.

He reached out to ASA founder Steph Sherer and ultimately co-founded Canadians for Safe Access, modeled on ASA, to advance reforms there. It would become the largest medical cannabis patient rights organization in Canada. He would go on to present about his work and research at ASA conferences, and now serves on ASA’s Advisory Board.

After 10 years, Philippe left VICS to focus on municipal community building, winning election to city council and then regional government as he continued his PhD work. He also became the second fulltime employee at Tilray, where he now leads a variety of international patient research projects, working with scientists at NYU, Columbia, and UC San Diego, as well as in Australia, Canada and the EU.

“Being part of the healing process for patients at VICS was a unique experience, but only a few thousand could benefit,” Philippe says. “Now, working with Tilray and internationally, I have the privilege of helping tens of thousands of patients around the world.”

Cost coverage for medical cannabis is now one of Philippe’s primary concerns. All major insurers in Canada offer coverage as an option for employee plans, and all Canadian police and military veterans have the cost of medical cannabis covered by Veterans Affairs Canada through Blue Cross. Covering medical cannabis creates a new cost for insurers, but each year that coverage has increased, there has been a significant decline in the number of prescriptions for opioids and benzodiazepines in Canadian veterans.

“In 25 years, we’ve gone from illicit substance to essential service, but stigma remains an ongoing challenge,” Philippe says. “One in 5 doctors have recommended cannabis to a patient, which is great, but that also means 4 in 5 have not. Most general practitioners are still not considering it.”

Via surveys, prospective studies and clinical trials, Philippe continues the work of translating the voice and experience of patients into data that inform policies and increase safe access to medical cannabis for patients in need.

“Nearly everything we know about medical cannabis is because brave, determined patients shared their experiences,” Philippe says

This profile was originally published in the May 2021 ASA Activist Newsletter

Share this page